The birth of fluorescent light is part a story of invention and part one of acquisition. It begins in the mid-nineteenth century with Julius Plucker and Heinrich Geissler, who were interested in the behaviour of gases within vacuums. In addition to being a physicist, Geissler was also a skilled glass blower, and together he and Plucker managed to make gas-filled glass tubes glow. A series of inventors followed, including D. McFarlan Moore, who stimulated a tube of carbon dioxide with an electric current; Peter Cooper Hewitt, who did the same to mercury vapor; and Georges Claude, who became the father of neon lights. But it’s German inventor Edmund Germer who is most widely credited with the invention of the fluorescent lamp. Germer’s design, which included coating the inside of the glass tube with a compound that converted uv light to visible light, was more energy efficient than any of its predecessors. He patented the design in 1926.

But Germer is not a household name the way Thomas Edison is, perhaps in part because he did not retain his patent for long. It was purchased for $180,000 by General Electric, Edison’s company, in the race to commercialize the fluorescent lamp. Under the supervision of George Inman, a team of General Electric scientists produced the first practical fluorescent lamp, laying the groundwork for a light source that is still prominent today.

Fluorescent lighting owes its longevity not to the quality of its light—by most standards it emits a harsh, “ugly” light that has been known to cause eye strain and headaches—but to its low cost and efficiency. As a result, fluorescent lights are most common in spaces that favour productivity over comfort—spaces like warehouses, schools, and of course, offices.

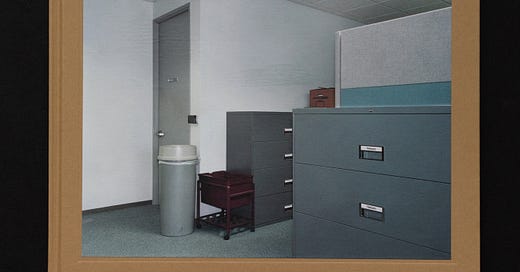

It’s the last that I’m interested in. The fluorescent light is as essential to the aesthetic of commercial office space as beige cubicles, white walls, grey carpeting, and filing cabinets. And though many of the photographs in Lars Tunbjörk’s Office appear to be lit by strobes, it is the hum of fluorescent lights that fill each page.

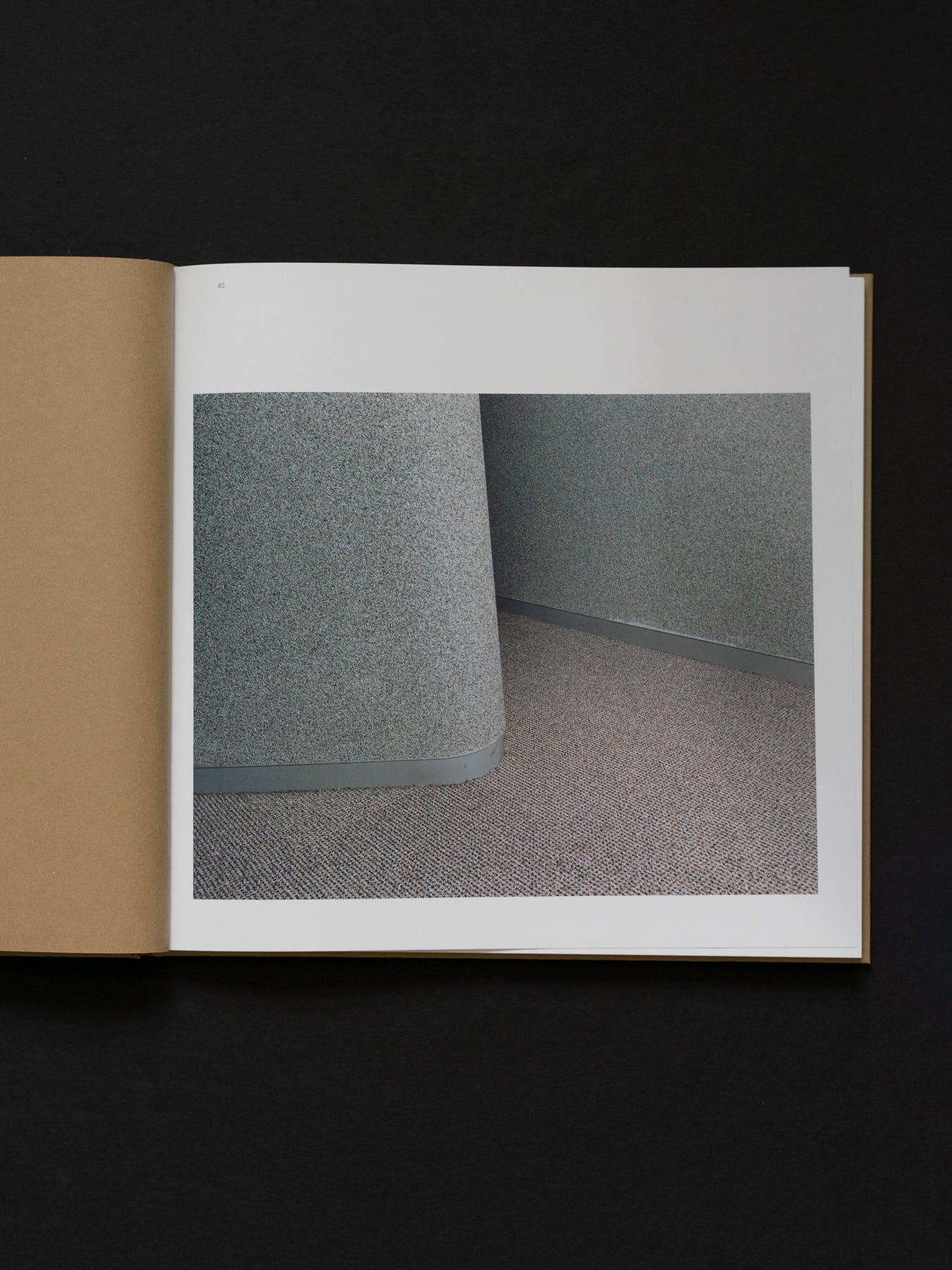

Tunbjörk spent five years documenting office spaces in Stockholm, New York, and Tokyo at the end of the 20th century. Office, first published in 2001 and reissued last year by Loose Joints, is the product of that work. The book begins with a photograph of grey cubicle walls and uncomfortable-looking carpet. When looked at abstractly, the scene could be a street corner. The cubicles stand like tall buildings (one could even be the flatiron building), and the spaces between them form roads or alleyways. The shapes in the image echo human structures, and as a result, human ways of living, but they are also grey, lifeless.

This is Tunbjörk’s approach throughout the book: He makes familiar objects, rooms, and people feel icily distant and inhuman. Spaces that many people spend a third of their life in look like the inside of an alien ship.

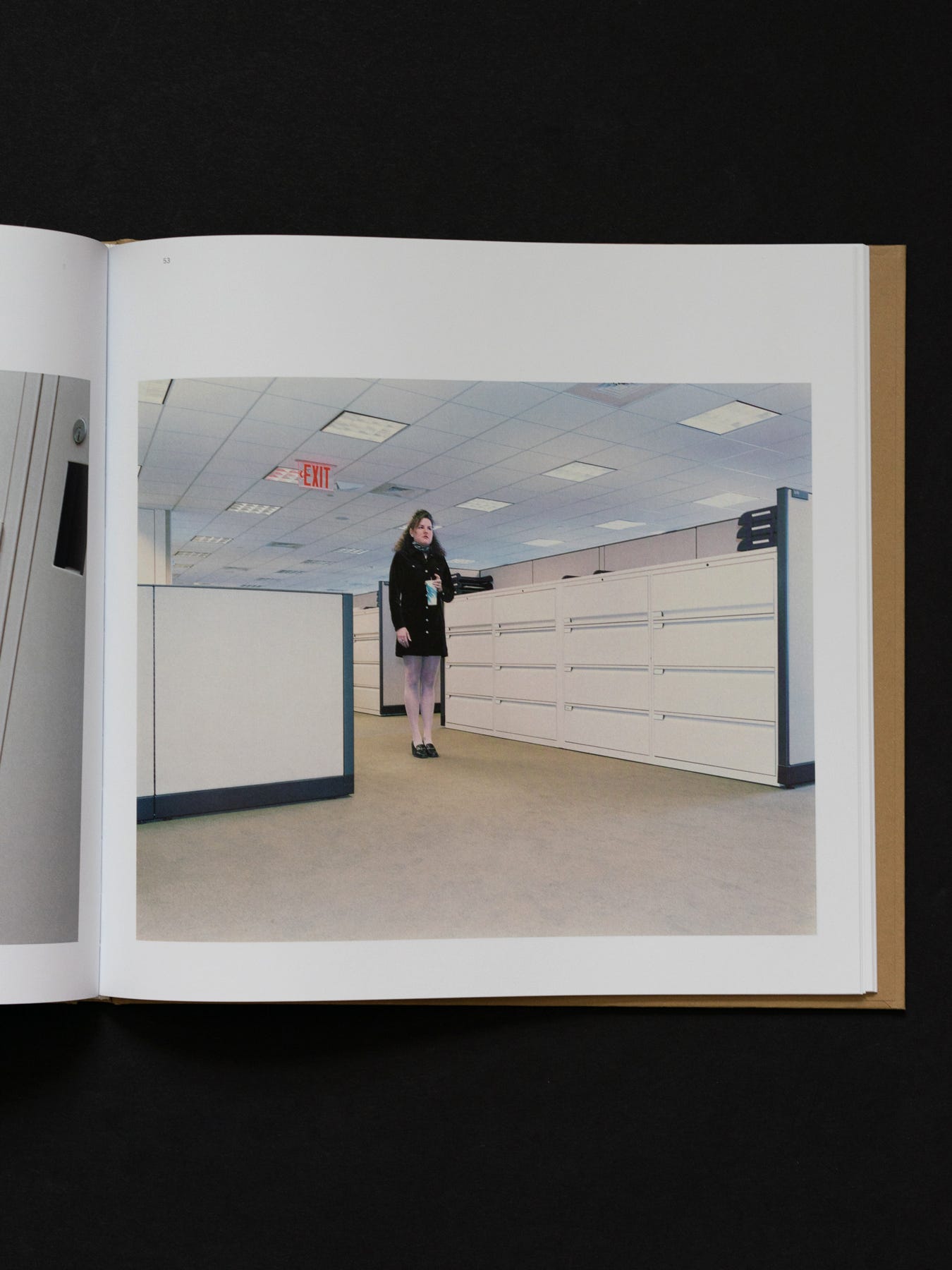

The second image in the book expands on the world Tunbjörk has created, pushing it from cold to downright strange. Unlike the first photograph, this one is a wide shot of a nondescript room lit by rows of fluorescent lights. The carpet appears blue, as do the cubicles and the roof. In the foreground, a woman stands inside a cubicle, next to a photocopier. Her head is turned away from the camera giving her an anonymous, almost robotic presence. The image is unsettling. The room feels like it could go on forever, and the woman, huddled in the corner, feels like she is hiding—or perhaps just doing what she is told. It’s hard, looking at the photograph in 2025, not to think of Severance, the AppleTV show about a group of office workers who have their personal selves and their work selves cut off from one another. What that show does with plot, Tunbjörk does with visual language. He reveals spaces that are meant for productivity and profit margins, not for personhood.

Yet people fill the book. They are sitting at computers, standing in corridors, or in one unusual image, sitting under a table. But rarely are the people in Tunbjörk’s images not working. They eat at their desks, sleep at their desks. They rush frantically from one place to the next. They adopt the efficiency of their surroundings.

In an essay about Office, Cal Newport compares Tunbjörk’s book to Office Space, the Mike Judge film from 1999. Each is trying to reveal something about the titular environment. Judge, Newport says, is laying the woes of office life at the feet of the managerial class, whereas Tunbjörk shows us a world of technological oppression—piles of computers, endless bundles of cable. But there is also the question of aesthetics in Office, of design. The book shows us spaces designed to maximize output. But profit, intangible as it is, is invisible in the work. We only see robotic office workers buzzing about in sterile rooms. In this way, Tunbjörk has achieved a severing of his own—action from outcome, means from end. The effect is haunting in part because it seems so senseless in his photographs. What are these spaces? Why are these people doing what they are doing? The answer, equally intangible, is simple: faster, cheaper, more.

I’d love to see this book in person some day.